We use cookies to provide you with the best possible service and a user-friendly website.

Please find our Privacy Policy on data protection and data management here

Please find more information on the cookies here

Are you coughing? Sneezing? Make sure it’s into your handkerchief! – A selection of our poster collection

With the lifting of the pandemic measures the old routines of everyday life are slowly returning, but much has changed. Now various announcements, posters, and notices propagating the correct form of behaviour are permanent parts of our everyday lives: keep your distance, put on your mask, only sneeze into your elbow or a handkerchief. Along with this an old, tried and tested genre of poster art, placards to educate the public about health issues, have now been given a new lease on life. The zenith (so far) of the genre was the 1960s when posters even exhorted people to wash their hands before eating.

It is a little known fact that in the poster collection in the Department of Prints and Drawings of the Hungarian National Gallery there are 18,000 posters in addition to the work of other graphic designers (ranging from the designs for printed material to leaflets). Among this rich material, which can rarely be viewed, are pieces that appear to be in harmony with the situation of recent months.

Stations

- Béla Sándor: Brázay Alcohol Rub, 1899

- Unknown: Lysoform, the Carpathians, our two giant supports, 1915

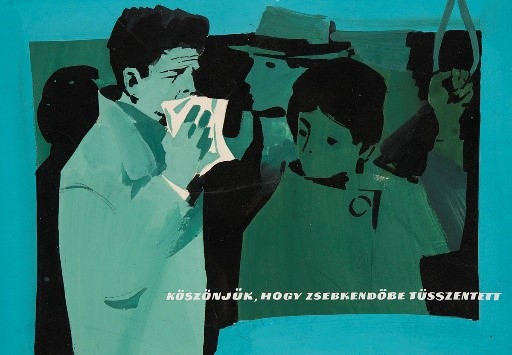

- Antal Gunda: Are you coughing? Sneezing? Make sure you do it into your handkerchief!, 1968 (original tempera design and poster)

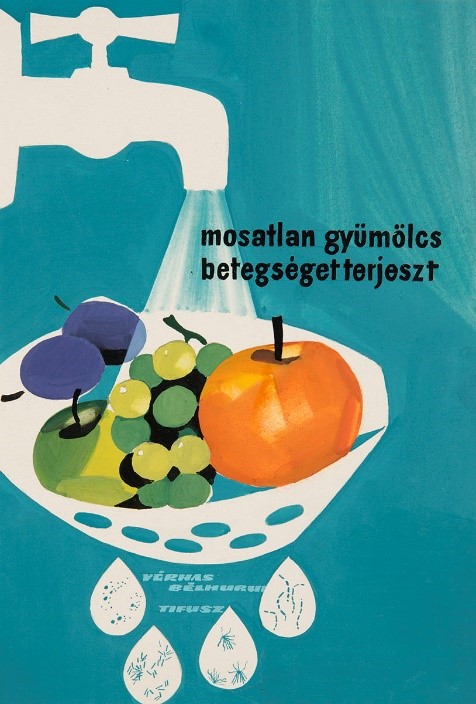

- Antal Gunda: Unwashed fruits spread germs, 1961

- Tibor Gönczi-Gebhardt: Clean village, healthy residents, 1961

- Tibor Gönczi-Gebhardt: Always have these things at home, 1972

- György Konecsni: Health protection during the rebuilding, 1945/1948

Béla Sándor: Brázay Alcohol Rub, 1899

Hand disinfecting up to the elbow

Let’s travel just a little way back in time. Disinfecting your hands these days seems like something new, but it goes way back. And of course, in this area, there are Hungarian inventions too, such as, for example, the famous “alcohol rub”.

It is not likely that alcohol rub would come up to par nowadays against COVID since it is actually just a preparation using nothing more than water, table salt, alcohol, ethyl-acetate and menthol crystals. In the past, however, it was seen as a universal wonder drug alongside disinfectant whether used to treat pain, rheumatism or for cleaning teeth. Although it was “invented” by Kálmán Brázay, it must be admitted that he only developed it further from a concoction that had been used by French peasants from the 1700s.

Brázay was truly a self-made man (his father fought in the War of Independence of 1848–1849 and the family lost everything), but after studying pharmacy abroad, he worked his way up the ladder and became the manager of a wholesale grocery business. The wonder drug was a commercial success and soon became a household name, being sold in the groceries of even the smallest villages. Poor healthcare and the advertising campaign carried out by Brázay both could equally play a role in this.

In 1899, Zoltán Brázay, the son of the manufacturer and founder, who had already been successful by that time, , issued a poster competition. Béla Sándor won second prize in this competition for his delicate Secessionist work characterised by subdued colours and decorative play with lines. The majority of the alcohol rub posters were not designed by him but by Hellman Mosonyi-Pfeiffer (who was awarded the first prize), and their common feature was that they generally depicted men – even though, as today, advertisements for cosmetics typically tended to use female figures. The elderly man, intently rubbing his body, must have represented the main target group while lending the desired prestige to the product.

Unknown: Lysoform, the Carpathians, our two giant supports, 1915

What can we rely on?

Just like nowadays, upon the outbreak of World War I, there was a sudden demand for disinfectants. After all, everybody wanted to look after their loved ones – as they do now – who were exposed to danger and if nothing else, it might help if they sent a bit of disinfectant to the men in the trenches.

The use of Lysoform, a disinfectant, was widespread. It was a potash-soap dissolved in formaldehyde, which had to be mixed with water. It was originally developed in Germany and first manufactured in the Monarchy in the early 1900s in the Budapest factory of Iván Murányi and Dr Kornél Keleti.

So in what way is this a war poster? According to the slogan, this excellent disinfectant would protect people from the war and every trouble at least as much as the Carpathian Mountains.

Sadly, neither of them protected people enough. After the war, the borders were redrawn and no longer defined by the Carpathians (exactly a hundred years ago). The owner of the Lysoform factory, Iván Murányi, enlisted himself and died of blood poisoning in 1916.

Antal Gunda: Are you coughing? Sneezing? Make sure you do it into your handkerchief!, 1968 (original tempera design and poster)

Handkerchief!

“Half-way down the road of human life, many people start to wonder if they have lived a good one. Deep in contemplation, philosophising, reading, asking for advice, debating and looking for the right way, instead of reading the texts of the posters on trams and buses. These little posters give people such useful advice that whoever lives according to them will never again find themselves in a mire of mistakes and blunders. … Ever since I switched to using the most modern rodenticide, rats have not dared come close to me, while I cough and sneeze into my elbow and I ask that others do the same.”

The lines above originate from the most popular humorous newspaper of the socialist period, Ludas Matyi (Mattie the Goose-Boy). In the second half of the sixties, this subtly scathing tone directed at official announcements was already tolerated; or at least in a paper otherwise committed to the system.

Antal Gunda: Thank you for sneezing into your handkerchief, 1968

Today we are again living in times when our most basic forms of behaviour (for example, when we cough) have to be advertised all around. But why was this necessary in the second half of the sixties, when, although in the midst of the Cold War, there was no threat of a global pandemic? It is difficult to find an answer to this: maybe only a few people knew what a handkerchief was? The Health Information Centre of the Ministry of Health (the logo of which can be seen on the poster) had to use up its advertising budget on what it could. It exhorted people to give blood and go to cancer screening and produced a stream of propaganda against smoking and drinking, etc., so hygiene issues could hardly be left out of this.

Why are the two pictures here almost identical? One of them is a hand-painted design, while the other is a poster of which 15,400 copies were printed (see the number at the bottom of the poster). Both of them can be found in the Hungarian National Gallery’s collection, thanks to Mrs Antal Gunda, who donated her husband’s legacy along with some quite special, original designs. This provides an opportunity for us to observe the changes between the design prepared for jurying – and in this case approved – and the final offset poster.

Antal Gunda: Unwashed fruits spread germs, 1961

Street art

Here are another two works by Gunda: a design and a finished poster. In 2015, the Hungarian National Gallery organised an exhibition from the master’s oeuvre in the Graphic Cabinet, titled From the Drawing Board to the Advertising Column, where these two works were also on display. The tempera design is a little more detailed and gives a list of illnesses, even illustrating them in the falling drops of water. (According to this, although Corona could not be caught from unwashed fruit, dysentery, enteritis and typhoid could.)

In 1961 Magyar Nemzet (Hungarian Nation) published an article analysing the poster scene, in which it praised the unwashed fruit poster for its “artistic colour effect”. It appears that at that time art critiques of such subjects appeared in the daily papers and that posters were very much regarded as street art.

Antal Gunda: Unwashed fruits spread germs, 1961

Antal Gunda’s career ripened into maturity in the sixties, and like most graphic artists of the time, he also began his career as a student of György Konecsni. The entire generation of Konecsni students started their careers at this time and made Hungarian poster-making outstanding (for example, the members of Papp’s group).

As the poster design also demonstrates, Gunda painted with a sure hand, while he also used techniques like montaging and glueing in other works. He produced figurative and painterly compositions that were modern at the same time, and of course not just propaganda posters but a great many posters for films too. He was not alone: in this period this was the average practice in Hungarian graphic design, bringing recognition and prestige while also being profitable. Even if ordinary people already knew that fruit should be washed, they could still enjoy looking at the posters.

Tibor Gönczi-Gebhardt: Clean village, healthy residents, 1961

What else should we keep in mind?

Socialist propaganda dealt with every facet of life; thus, examples can easily be found in the Hungarian National Gallery’s poster collection that rhyme with our new experiences of the last few months.

For example, public hygiene was part of the healthcare information campaigns, which is illustrated in a poster by the famous graphic artist, Tibor Gönczi-Gebhardt from 1961. After 1956, poster art was able to leave behind the obligatory, photographic realist style of social realism as well as its mandatory topics. In the first years, painting was still a dominant technique, and figurative styles continued, but depictions became more modern and stylised as Gönczi’s playful, light-hearted poster also demonstrates.

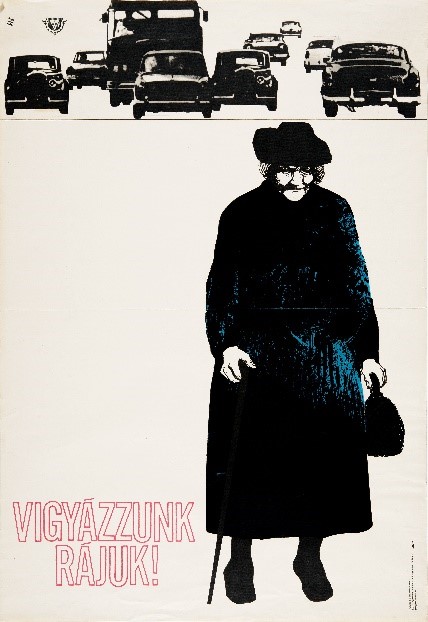

Margit Sándor’s work is about protecting the elderly, though it concerns their safety on the roads, while today it is rather about helping them to stay safe at home. This poster was made in the sixties, in the heyday of poster-making, when all manner of new techniques were employed in design. For example, here we can see the use of photomontage.

Margit Sándor: Look after them!, 1967

Tibor Gönczi-Gebhardt: Always have these things at home, 1972

It is worth noting that by the seventies a lot of flat, boring works were (also) produced in poster art trying to find its way. Gönczi-Gebhardt’s poster encourages people to stock up (and who didn’t give in to the urge to shop and stock up during the first weeks of the lockdown, to have enough drinks and cake at home?). This poster was actually a commercial advertisement and advertised KÖZÉRT, the state-run grocery chain. Since there were barely any competitors nor any real market competition to speak of, the only purpose this commercial poster could have had was to boost consumption.

György Konecsni: Health protection during the rebuilding, 1945/1948

A new beginning

Finally, the time has come when life can restart. Carefully, of course, while following the rules, but ordinary life is slowly returning.

In 1945, after the war, everything had to start again from a much more horrid low point. The country was in ruins, and Budapest, which had suffered a siege, was especially hard hit by the fighting. After the enormous suffering and the innumerable victims of the Holocaust and the war, it was a new beginning, starting slowly but surely. Encouragement was sorely needed and many posters proclaimed a new beginning.

The final work displayed here is a poster design which was never completed: it is a large-scale, subtle work, painted in tempera on cardboard. Using only a few motifs, it expresses the broken spirit that is nevertheless bent on trusting and wanting to believe in life.

The artist is György Konecsni, who is regarded as one of the foremost masters of Hungarian poster art. His activities were dominant in Hungarian graphic design as early as the thirties, when he mainly designed posters for the tourist industry. In the period between 1945 and 1947, his dramatic works propagated the most important issues of the new period as well as the parties participating in elections.

Konecsni, a painter-cum-poster designer, produced works that were often rather paintings than graphic art. He was an extremely productive artist and it is exceptionally fortunate that his heirs carefully preserved his legacy, which includes canvases and designs. It is wonderful that they donated several pieces from his collection, ones regarded as curiosities, to the collection of the Hungarian National Gallery; for example, this poster design, which was never realised.